Go Back

Morris: An Ugly World Is Costly

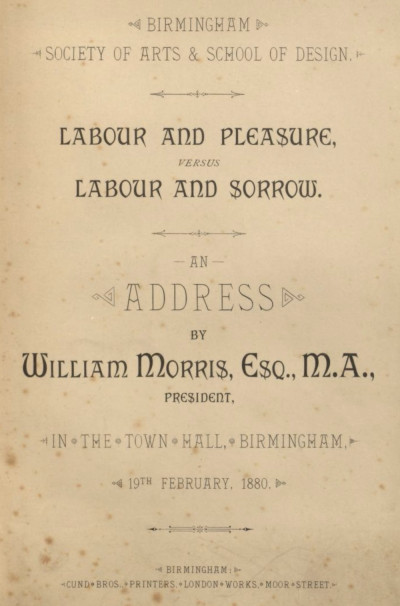

Those familiar with William Morris are usually aware of his golden rule: Have nothing in your houses which you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful. That maxim was announced in a speech he gave called Labour and Pleasure Versus Labour and Sorrow (later printed with the title The Beauty of Life in a collection called Hopes and Fears for Art). That one line stands out as his central piece of advice that has been quoted as generations passed, but the speech is full of gems worth exploring on every page.

(Morris' words are set in boldface.)

Morris was 45 when he addressed the crowd at The Town Hall in Birmingham, England, and he called himself an ‘old hand’ in the realm of art. Granted, he certainly sounded like a crotchety old man at moments in the speech, bolstered by his liberal use of bellicose analogies.

Morris presented a swirling litany of problems throughout the address, coalescing around his main purpose: the democratization of art. He desired that all social classes should participate in making the world beautiful. A scandalous idea, perhaps, in the firmly classed monarchical society of Victorian England.

PEOPLE ARE LIVING AS HALF-HUMAN

Morris began by addressing the problem as he saw it: the debasement of humanity, forced to inhabit an increasingly ugly world. Art was his solution. Art, in as broad a scope as we can imagine it, he declared, survives the birth and death of empires and infuses life with Romance. It is a ‘positive necessity’ if we want to live a rich and flourishing life. To Morris, art had been driven out of quotidian experience—at least in part—because fewer folks were interacting with handcrafted goods. The now-solidified factory system was churning out lower quality, mass produced products at cheaper prices. Nothing, he thought, about this new(ish) dilemma exhibited an elevation of daily living art should produce.

Industrialization was surging again as England began competing with newly developing nations in the 1880s. Any hope of diminishing the myriad negative side effects of that growth was quashed as economic struggle accelerated. The workmanship of goods leaving the new factories became ever more rote and pedestrian in Morris’ eyes, and he declared

whereas all works of craftsmanship were once beautiful, unwittingly or not, they are now divided into two kinds, works of art and non-works of art: now nothing made by man’s hand can be indifferent: it must be either beautiful and elevating, or ugly and degrading; and those things that are without art are so aggressively; they wound it by their existence

‘Modern civilisation,’ he said, ‘is on the road to trample out all the beauty of life.’

AN ASIDE ABOUT SMOKE

The factories were doing more than producing materials that lacked the art of previous handmade goods; they were making the and. itself ugly. On this assertion, Morris was far from alone. England had been fighting smoke problems from coal fires and manufacturing on and off for centuries. That soot staining had largely been relegated to the urban areas of the country until the 19th century. The black blanket grew, though, as manufacturing took over the north of England.

Parliament deputized local governments to create regional rule. Local councils, reluctant to contend with their new manufacturing behemoths, passed policy expectations back to the national level. Both levels of government attempted to enact legislation down multiple avenues of industrial regulation. However, most codes on the books lacked the enforcing teeth to make them useful. Many of the major smoke producing industries like potters and smelters were able to arrange exemptions, or they would pay the minimal fines required to keep their fires burning at full capacity. In the mid-1860s a report to Parliament indicated some regions of the countryside could scarcely be seen through the smoke.

Three years prior to Morris’ speech, the Inspector of Smoke Nuisance (his actual title) Samuel Sands wrote a brief section in the Report on the Sanitary Condition of Leeds for the Year 1877:

I would simply remark in relation to the Smoke nuisance, that until we obtain some power over the greatest producers of Smoke nuisance, we shall hardly see any marked improvement in the atmosphere of large manufacturing towns.

At almost any hour during the day a dark gloom—sufficient to produce a melancholy—hangs over two districts in Leeds…Those districts suffer almost daily and hourly from a canopy of dense smoke. As long as this division of trade is allowed to escape from the laws preventing nuisances, I cannot see that much improvement will ever be observable from a partial Act like the Smoke Acts. Whilst those trades, the Iron trades I mean specially, are flourishing most, our towns become blackened, and all the pleasing and cheerful influences of vegetation and foliage are swept away.

THE BLAME GAME

Morris saved some of his harshest words to lambast the monied elites (to whom he belonged), especially those captains of industry who commanded the smoke producing factories. Those, he said, who claimed to appreciate art.

I say that their love of art is a mere pretence: how can you care about the image of a landscape when you show by your deeds that you don’t care for the landscape itself? or what right have you to shut yourself up with beautiful form and colour when you make it impossible for other people to have any share in these things?

Rather, he said, they ‘profess to wish to further the arts; but you see it must be idle pretence as far as their rich people are concerned: they only want to talk about it, and have themselves talked of.’

Morris granted a bit of neglectful slack to the working class, partially by allowing that they bore the weight of working the production lines in the ugly-making factories with little access to the level of education that could inspire a newfound sense of beauty. People who claimed fine education, though, received no reprieve from him:

the murder of art [that] curses our streets from the sordidness of the surroundings of the lower classes, has its exact counterpart in the dulness and vulgarity of those of the middle classes, and the double-distilled dulness, and scarcely less vulgarity of those of the upper classes.

—and—

rich people have defrauded themselves as well as the poor: you will see a refined and highly educated man nowadays, who has been to Italy and Egypt, and where not, who can talk learnedly enough (and fantastically enough sometimes) about art, and who has at his fingers’ ends abundant lore concerning the art and literature of past days, sitting down without signs of discomfort in a house, that with all its surroundings is just brutally vulgar and hideous: all his education has not done more for him than that.

Regardless of their wealth no one is immune from the ugly, un-artistic state of the world, Morris claimed (with more than a touch of delicious self-satisfaction). Anyone, he said, who thinks they can hide from the world with their education and cultured ideas and exchanges ‘are as it were living in an enemy’s country; at every turn there is something lying in wait to offend and vex their nicer sense and educated eyes: they must share in the general discomfort—and I am glad of it.’

THE REMEDY: ART IN EVERYTHING

Morris, of course, had a solution: redefine the idea of civilization and spread it to all, which would happen in part by all of society participating in art. That is, making everything needed for daily life to be useful and beautiful.

As a man who initially planned to be an architect, and changed tacks primarily to home furnishings like textiles, Morris wanted the democratization of art to begin—perhaps obviously—with homes. He insisted architecture is the most fundamental of the arts, and we cannot progress into finer arts until we’ve learned to make art of our dwellings.

To that end he argued for a limit to furnishing a home—only what is needed for daily life and work. He called that simplicity: the simplicity that comes from excising ‘troublesome superfluities’ from your living spaces. How that simplicity was executed he left to the individual:

The simplicity you may make as costly as you please or can… you may hang your walls with tapestry instead of whitewash or paper; or you may cover them with mosaic, or have them frescoed by a great painter: all this is not luxury, if it be done for beauty’s sake and not for show: it does not break our golden rule: Have nothing in your houses which you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.

Furthermore, these beautiful necessities must be made by people who have been able to invest their whole person in the process. ‘Take care that there be no sham art amongst them,’ he said. That is, ‘nothing that it has degraded a man to make or sell.’

Though Morris was addressing one specific group over 100 years ago in Birmingham, England, the thrust of his rallying cry resounds into today. That struggle: the rebirth and spread of free thought and common bonds through the art of our everyday experience—that, he said, was the responsibility of everyone, whether they realized it or had any interest in participating:

for as every age of the world has its own troubles to confuse it, and its own follies to cumber it, so has each its own work to do, pointed out to it by unfailing signs of the times; and it is unmanly and stupid for the children of any age to say: We will not set our hands to the work; we did not make the troubles, we will not weary ourselves seeking a remedy for them

Morris finished by repeating his call to join the battle, and to commit to a life of beautifying the world. His words echo Abraham Lincoln’s nearly two decades prior during the commemoration of the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania:

but surely since we are servants of a Cause, hope must be ever with us, and sometimes perhaps it will so quicken our vision that it will outrun the slow lapse of time, and show us the victorious days when millions of those who now sit in darkness will be enlightened by an Art made by the people and for the people, a joy to the maker and the user.

Post script:

What, then, did Morris personally find beautiful? Among other things: the medieval. These Old California fixtures rely on a medieval aesthetic within the Arts and Crafts philosophical tradition. We think Morris would approve.

Post post script:

Morris bounces between more topics than can be noted here: his love of old buildings (he had recently founded the Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings), the increasing prevalence of advertising posters, littering (a ‘sluttish’ behavior he found ‘so vexatious’), and the cost of civilization due to our misunderstanding of what it means to have a flourishing society. Read the full printed edition courtesy of the McGill University Library here.

Post post post script:

Indeed, there is nothing new under the sun—

Alain de Botton discusses why he thinks the world is still ugly in one of his School of Life videos.

Morris wanted to democratize art and beauty. Botton claims we’ve democratized comfort. Listen to Botton discuss our world of ‘brutal boxes’ in a voice that is probably more soothing than Morris’ ever was.

Watch it here.